The first Spanish soldiers and missionaries of Alta California endured many hardships since their arrival in San Diego. The first settlement on Presidio Hill was a mere hospital camp where most of the early colonizers perished from scurvy and other miseries. What follows is the account of how the first Spanish colonizers founded the two earliest missions and forts, or presidios, in Alta California.

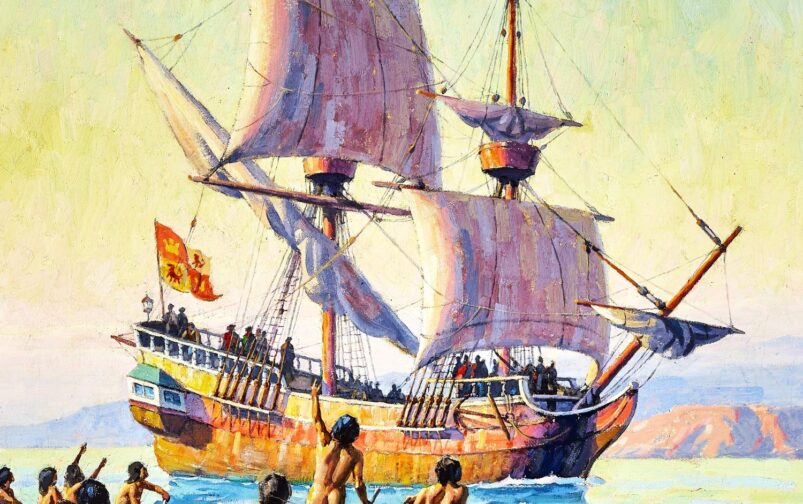

Two Spanish sloops arrive in San Diego Bay

The San Antonio was the first ship to reach the shores of San Diego, on April 11, 1769. Nearly three weeks later, on April 29, the San Carlos was put ashore in San Diego Bay. Most of the men onboard, especially those on the San Carlos, which had sailed unremittingly for almost four months, were sickened by scurvy. The San José, a third ship packed with goods and supplies, would never arrive.

Exploration of San Diego Bay

On May 1, Lieutenant Pedro Fages, cartographer Miguel Costansó, and Jorge Estorace along with 25 sailors and soldiers still able to work came ashore. They went around exploring the nearby area in search of a source of fresh water and a suitable location to camp. With the help of local Indians, they discovered a river nine miles northeast of where the San Antonio and the San Carlos were anchored. On May 4 and 5, they moved the two ships as close as possible to the chosen area inside San Diego Bay, today known as Spanish Landing, and set up a camp on the beach.

The hospital camp in Spanish Landing

The camp consisted of an earthen parapet with two cannons, two large hospital tents for the sicks made using the ships’ sails, and smaller tents for the friars and officers. Once the camp was ready, they started moving the ill men to shore and settled them in the camp. Doctor Pedro Prat, the expedition’s surgeon, tried his best to save the lives of the sickened men. But he had run out of medicines and was weakened himself by scurvy. On the beach camp, the ill men were exposed to hot days and cold nights. Two or three men passed away every day in the camp. Out of the 92 who had embarked on the San Antonio and San Carlos sloops, only sixteen survived, eight sailors and eight soldiers.

The first European settlement in California

On March 14, 1769, Captain Fernando Rivera and his group arrived at the beach camp after trekking for fifty days and 300 miles (480 km) from Velicatá. They were the first Europeans to reach San Diego by land. Although Rivera’s party had nearly finished its food rations, not a single man was lost on the journey. All men arrived in San Diego in reasonably good health conditions, although exhausted and emaciated. The same day, Rivera and his men moved the camp inland near the San Diego River, on a hill that would become known as Presidio Hill. Today, the hill is part of Presidio Park and it is located just above Old Town San Diego. Here, they erected a stockade and placed a cannon on the spot that would later become the Royal Presidio of San Diego, the first European settlement in California. Two weeks later, the last group traveling by land headed by Portolá and Junípero Serra also arrived in San Diego.

Portolá and Father Serra arrive in San Diego

The same day of his arrival at San Diego on July 1, 1769, Portolá established a small garrison on Presidio Hill, near the Kumeyaay village of Kosa’aay, which the Spaniards would later call Cosoy. The outpost only consisted of a few grass huts and brush-covered enramadas. They brought some relief to the little camp as they brought with them 163 mules loaded with goods and supplies. Father Serra and Portolá found out that the outpost had become a hospital for the sick crew members of the ships. Despite the difficult situation, in his diary, Father Serra described the area of San Diego as a truly beautiful land with all he had hoped for. And so it was to his eyes. After traveling 5,000 miles from the island of Maiorca, in the Mediterranean Sea, the small and zealous friar had finally reached virgin lands inhabited by pagans, whose souls were ready to be harvested and brought under the Catholic Faith.

The San Antonio sails back with a crew of eight

As the group remained in desperate need of help and supplies, the San Antonio, under the command of Captain Juan Pérez, was urgently sent back to Mexico. On July 9, 1769, the ship left for San Blas with only eight men on board. Six crew members died on the way back but the ship miraculously made it to San Blas, informing the Viceroy and Inspector Gálvez of the desperate situation in San Diego. Governor Portolá considered San Diego only a stop on the way to the long-sought Bay of Monterey. Nonetheless, with most of the crew sick and incapacitated, he had to abandon the idea of reaching Monterey by ship.

Portolá leaves San Diego in search of Monterey

After resting for two weeks, on July 14, 1769, Gaspar de Portolá left San Diego with sixty-two men to march northward on foot. Fathers Crespí and Gómez departed with him, leaving to Father Serra the task of founding the first mission of California near the small garrison. Other than Fathers Crespí and Gómez, the Portolá party consisted of two army officers, Fages and Costansó, Sergeant Ortega and twenty-six soldiers, Rivera and six surviving Catalan volunteers, fifteen Baja California Indians, seven muleteers, and two servants.

The ship San Carlos remained anchored in the bay. On board, there were Captain Vicente Vila, the second pilot José de Canizares, two soldiers, and a few convalescent sailors. On Presidio Hill remained three Franciscan missionaries, Serra, Fernando Parrón, and Juan Vizcaíno. With them were also Dr. Pedro Prat, eight Indians from Baja California, one servant, a blacksmith, a carpenter, a corporal, a handful of Spanish soldiers, and several sick men lodged in the field hospital.

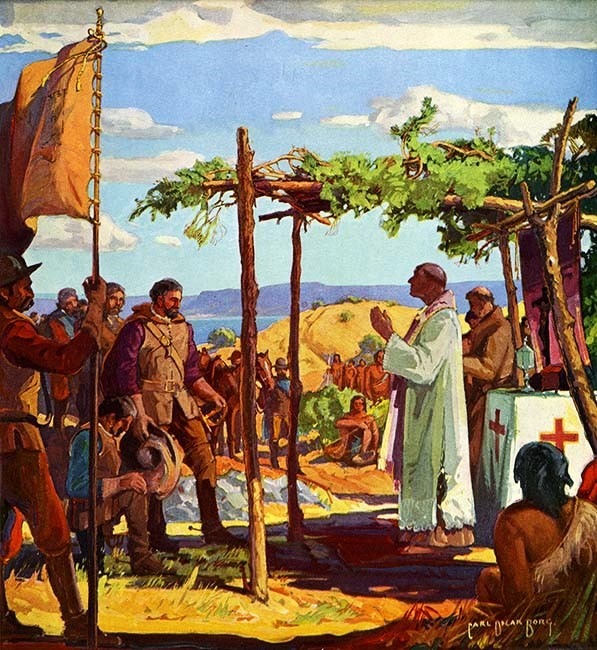

Father Serra founds the first California Mission

Two days after Portolá had departed, Father Serra called upon those who still had their strength. A small chapel was built on Presidio Hill out of wooden stakes and tule reeds used for roofing. The party raised a crude cross and, on July 16, 1769, Father Serra sang High Mass and founded Mission San Diego de Alcalá, after St. Didacus of Alcalá, whose name had been given to San Diego by Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1602. The first of all California missions had been founded.

Troubles between the new mission and local Indians started immediately. The Franciscan Fathers tried their best to establish a good relationship with the local Kumeyaay Indians, treating them with kindness and offering them small gifts. Nonetheless, once their initial curiosity about the white invaders was satisfied, the Kumeyaay started to become insolent and aggressive. They started pestering the hindered men and stealing everything they could from the Spanish camp, being especially fond of clothes. On one occasion, they reached the San Carlos on rafts and tried to steal the sails. Spanish guards had to be placed on the ship and two more guards began to escort the Fathers who went onboard to say Mass.

A group of Kumeyaay warriors attacks the mission

As days passed, more and more Spaniards died from the effects of scurvy. The diminishing strength of the garrison emboldened the Natives and it soon became clear that an attack of some sort was imminent. Indeed, the attack arrived on August 15, 1769, at the Feast of the Assumption. The Kumeyaay noticed that four Spanish soldiers had left the garrison in the direction of the beach to bring Father Fernando Parrón back from the San Carlos, where he had been celebrating Mass. Only four soldiers remained on Presidio Hill. At that moment, a group of over twenty Indian warriors armed with bows and arrows attacked the garrison. The four soldiers, the carpenter, and the blacksmith Chacón, returned fire with muskets and pistols.

Serra’s servant Vergerano dies during the attack

As the first shot was heard, Serra’s servant, José María Vergerano, reached Father Serra in his hut. His neck had been pierced by an arrow and he was completely covered in blood. Father Serra had just the time to absolve him. Vergerano passed away before Serra’s eyes, lying on the ground and bathed in his blood. Three Kumeyaay were killed during the attack and a number were wounded. Two of them would later die from the wounds. Father Vizcaíno, the blacksmith Chacón, and a Christian Indian from San Ignacio were also injured although not seriously.

The Spaniards erect a stockade on Presidio Hill

After the attack, the Spaniards hurried to finish building a wooden stockade all around the compound and forbade entrance to the Natives. On the other side, the Kumeyaay warriors had retreated with a newfound respect for the power of firearms used by Spaniards. The Natives settled down and for a while started ignoring the Spanish party. This came as terrible news to Father Serra as his efforts to convert the Natives to Christianity were nullified.

The episode of Serra’s frustrated baptism

Almost in desperation, once a group of Indians carrying a naked baby boy showed up at the mission, Serra interpreted their sign language as a desire to have the boy baptized. He asked the corporal of the guard to sponsor the baptism and, as soon as he lifted the baptismal shell filled with holy water and started pouring it over the baby’s head, some of the Natives attending the celebration grabbed the little boy from the corporal’s harms and ran back to their village in fear. The other Natives assisting at the baptism followed them, giggling and jeering. Father Serra never forgot the incident of the frustrated baptism and years later he will remember it with tears in his eyes.

Several men die of scurvy on Presidio Hill

However, the three Franciscan missionaries left in San Diego had more urgent worries to solve as they were still fighting for bare survival. Before the return of the Portolá expedition, the Fathers buried one servant, six more Baja California Indians, four more soldiers, and eight more Catalan volunteers. All of them died of scurvy. The Fathers also started to realize that the supply ship San José would never arrive and gave it for lost.

Portolá reaches San Francisco Bay

Meanwhile, the courageous Portolá reached the bay of Monterey thirty-eight days after departing from Presidio Hill. But he failed to recognize the bay as, in his report of 1602, Sebastian Vizcaíno had greatly overstated its dimensions and its importance. Unable to reconcile the bay before his eyes with Vizcaíno’s description, Portolá left Monterey Bay and kept heading north on its search. On October 31, 1769, the Portolá expedition sighted the Farallon Islands and Port Reyes off San Francisco. They were able to recognize these landmarks on Vizcaíno’s maps and realized that they had overcome Monterey Bay. The next day, Sgt. Ortega and a small scouting group reached the shore of San Francisco Bay. Father Crespí noted that the bay was large enough to hold all the ships of Europe. Even though the huge harbor had not yet been reported by any of the earlier explorers, Portolá failed to recognize the importance of his discovery. He considered it only a mere impediment in his search for Monterey Bay. Nearly starving to death, Portolá and his men decided to return to San Diego.

Portolá returns to Presidio Hill

Over six months had passed when, on January 24, 1770, the men of the Portolá expedition emerged from Rose Canyon. On the way back to the Bay of San Diego, they had survived by slaughtering and eating their mules. During their absence, little had been done on Presidio Hill beyond the marking of 19 new graves but Portolá found that the three Franciscan friars were well and those who had survived were slowly recovering from scurvy. Portolá reported to Serra the existence of large groups of Natives along the coast that seemed friendly and collaborative. Immediately, Serra wrote a fervent letter to the College of San Fernando in Mexico, requesting more missionaries willing to spread Christianity among the Natives of Alta California. He discovered that Fathers Crespí and Gómez had performed the first baptismal ceremony in California, baptizing two Indian girls near Christianitos Canyon. Father Serra was to recall this episode with sadness until the day of his passing for he had not been the one to perform it.

The first settlers are running out of food supplies

Food scarcity remained one of the biggest problems at Presidio Hill. The Spaniards sustained themselves by eating geese and fishing. The Kumeyaay Indians also brought some food to the Spanish outpost in exchange for clothing. The Spaniards tried planting and growing some corn but birds ate most of it. Portolá decided to send Captain Rivera back to Baja California with instructions to return with cattle and a packed train of supplies. On February 10, 1770, Rivera left San Diego with a bunch of soldiers and started trekking down the peninsula. On Presidio Hill, they had no way of knowing if the San Antonio ship was on its way back or not.

California’s colonization efforts might be at an end

Portolá was becoming increasingly worried that his soldiers would have died of starvation in San Diego. After a long talk with Father Serra, a deadline was agreed. If a supply ship did not arrive at the harbor by March 19, the day of St. Joseph, the expedition would abandon Presidio Hill the next day and return to Baja California. Nonetheless, Father Serra felt that if San Diego was to be abandoned, another century would pass before it could be settled again. He secretly decided to remain in San Diego at any cost and confessed his intentions to Father Crespí, who agreed to stay with him. Captain Villa also confided to Father Serra that he had the intention to keep the San Carlos at an anchor in San Diego, as he thought that the harbor could still be held.

Waiting for the arrival of the ship San Antonio

Nine days before March 19, 1770, Father Serra proposed to all in the camp to begin a novena, nine days of prayer to obtain special graces, in time to end by the arrival of the fatidical day of St. Joseph, the patron saint of the expedition. A high mass had sung and a sermon preached and yet all the prayers came to no avail as, on the morning of March 19, no ship appeared on the horizon. Portolá and his soldiers began preparations to return to Velicatà. At around three o’clock in the afternoon though, the Spaniards on Presidio Hill began to discern the sails of a ship in the ocean. There were the sails of the San Antonio, returning to Alta California supplied with every provision. The San Antonio went past San Diego Bay but somehow everyone in the camp felt that their days of hardships had come to an end. Even Portolá decided to delay his return to Baja California for a few more days.

The San Antonio ship anchors in San Diego harbor

Four days later, the San Antonio anchored in the harbor of San Diego. The San Antonio was sailing to Monterey but on the way had lost an anchor near Point Conception. Furthermore, some crew members who went ashore in search of fresh water had been informed by friendly Natives that the land expedition directed to Monterey had returned to San Diego long ago. The Captain of the San Antonio, Juan Pérez, decided to turn back to San Diego to obtain an anchor from the San Carlos, knowing it was still in the harbor. Once again, the San Antonio lost most of his crew due to scurvy. Nonetheless, the ship brought rice, flour, and corn which meant salvation for the first European settlers of San Diego. After this episode, Father Serra celebrated a high mass on the nineteenth of every month to remember the saving of San Diego and the first mission in Alta California.

Portolá’s second expedition to Monterey

Bolstered by the food brought by the San Antonio, Portolá and his soldiers prepared a new expedition to reach the bay of Monterey which, as in the desires of Inspector General José de Gálvez, was to become the northern settlement in California of the Spanish Empire. Father Crespí joined the second Portolá land expedition to Monterey. The San Antonio would have set sail to Monterey as the sea expedition. Father Serra, who was suffering from an infirmity in his left leg, joined the San Antonio sea expedition together with Doctor Pedro Prat and Miguel Costansó.

The European settlers head for Monterey Bay

On April 16, 1770, the San Antonio left San Diego harbor sailing for Monterey. On April 17, Portolá also left San Diego trekking north. The land expedition included Captain Pedro Fages, Father Crespí, seven leather-jacketed soldiers, twelve Spanish volunteers, two muleteers, Portolá’s servant, and five Indians from Baja California. Fathers Fernando Parrón and Francisco Gómez along with other twenty-one men, remained on Presidio Hill in charge of the San Diego Mission and Presidio. On its way to Monterey, the San Antonio found contrary winds which blew the ship as far south as the Baja California peninsula and then north as far as the Farallon Islands. It took the San Antonio six weeks to sail to Monterey and many of the men onboard again fell sick with scurvy.

The Spaniards reach the Bay of Monterey

The Portolá land expedition reached Monterey on May 24, 1770, followed on May 31 by the arrival of the San Antonio. The same day of their arrival and with the hope of sighting the San Antonio on the horizon, Portolá, Father Crespí, and a soldier walked over the hills to Point Pinos first and then to a beachside hill located just south of where Portolá had planted a large cross five months earlier while, with his previous expedition, he was returning south from San Francisco. They found that feathers had been scattered and broken arrows driven into the ground all around the cross. Meat and sardines had been laid out in front of the cross. They did not meet any local Indians. They kept walking south reaching Carmel Bay where they met the first Natives with whom they exchanged gifts.

Serra founds the second mission of California

On June 3, 1770, a Pentecost Sunday, Father Serra, Portolá, and all the men gathered under a large oak tree standing in front of Monterey Bay. The oak tree had been earlier described by Sebastián Vizcaíno in his 1602 exploration of California and would later become known as the Vizcaíno-Serra Oak, or the Junípero Oak. Under the massive tree, the Spaniards erected a makeshift chapel and Father Junípero Serra held a solemn mass founding Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo, known at the time as San Carlos Borromeo de Monterey, the second mission in the chain.

The Royal Presidio of Monterey was also established on the same day. Since the beginning, Father Serra felt that the new mission needed to be relocated further south in Carmel Bay. The area of Carmel was indeed more suited because of the excellent quality of the lands, the proximity of water supplies, and the presence of friendly Natives. Furthermore, the Laws of the Indies, which regulated the settlement of American and Asian possessions under the Spanish Crown, dictated that the missions had to be founded near the villages of the Natives to facilitate their conversion to Christianity.

Portolá departs forever from California

On July 9, 1770, the San Antonio set sail from Monterey to return to Mexico. Governor Portolá and the engineer and cartographer Miguel Costansó were onboard along with many letters written by a fervent Father Serra and destined to the College of San Fernando in Mexico. Before sailing on the San Antonio, Portolá turned his command as Governor to Pedro Fages and left him with the duty of building the presidio of Monterey in an area previously identified by Costansó. And so it was that Portolá departed forever from the pages of California History.

The Spanish settlements are still at risk

Only forty men, including five Indians from Baja California and Friars Serra and Crespí, remained in Monterey Bay. 450 miles south, in San Diego, another twenty-three men were busy with the development of the first settlement. Both groups of early European settlers would have to wait another year before receiving aid and supplies from Mexico.

Pedro Fages builds the Presidio of Monterey

Unlike the easygoing Portolá, Governor Pedro Fages was a despotic ruler. He imposed strict discipline on his men, obliging them to work on Sundays and even under heavy rains from the winter of 1770 until the spring of 1771. In late June 1771, Fages sent a letter and a map of the new fort to the Viceroy of Mexico, Carlos de Croix, informing him that the Presidio of Monterey had been completed. The work had been done but the Spanish soldiers under his command felt dispirited and considered Fages a tyrant.

Soldiers’ complaints pushed Father Serra to confront Fages, reminding him that, as a Christian, he had to observe a sabbath and let his men rest on Sundays. Relationships between Serra and Fages would soon deteriorate. Some of the Spanish soldiers of the Monterey Presidio began raping the Indian women and taking them as concubines. After Serra’s urgent complaints, some of these excessive behaviors were punished but sexual abuses continued.

The second Mission is moved to Carmel Valley

It became clear that the two men couldn’t get along and before the end of 1771, Father Serra decided to relocate Mission San Carlos Borroméo across the peninsula in the Carmel Valley. The relocated mission also became known as Carmel Mission and served as Father Serra’s headquarters during his Presidency in Alta California.

Re-supply of Alta California proves difficult

Despite all the hardships and difficulties, a third and fourth missions, San Antonio de Padua and San Gabriel Arcángel were founded during the year 1771. Nonetheless, the very existence of these initial European settlements in California was threatened by the difficulty of receiving supplies from Mexico. The sea route from La Paz was too long and dangerous. The San Carlos, the San Antonio, and the lost ship San José had proved it. Moreover, the little sloops only had room for a minimum of supplies beyond their crew, while the settling of California required the arrival in force of new colonists. The most viable route remained the long land journey on mule trains from Baja California up to the peninsula until reaching San Diego. Moreover, most of the goods had to be manufactured and shipped to Baja California, one of the poorest areas of New Spain. It became obvious that alternative supply routes had to be found or California might be still lost.

Serra travels to Mexico City in search of support

On October 17, 1772, Father Serra left Alta California directed to Mexico City. He had the impellent necessity to clarify his authority in California and request further support for the new settlements. He confronted Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli and obtained the removal of Pedro Fages as Governor of Alta California. He also pointed out the necessity to find a new and easier land route to California. Help would come from explorer Juan Bautista de Anza who, in 1774, reached the San Gabriel Arcángel mission from Tupac, Arizona, thus establishing the first overland route from Mexico to California. The same year, Father Serra returned to Alta California and Fernando Rivera y Moncada replaced Fages as the new Governor of California. Once again, the relationship between Father Serra and the new Governor Rivera y Moncada would soon become problematic.

Franciscans can now focus on Alta California

On May 12, 1772, the control of Baja California missions was turned over to the Dominican missionaries. In 1773, Father Francisco Palóu, who had been administering the missions of Baja California on behalf of the Franciscans, left Baja California and traveled to San Diego with five other Franciscan missionaries. In August 1773, while Father Serra was still in Mexico, Father Palóu decided to move Mission San Diego six miles inland to lessen the difficulties the Padres were having with the soldiers on Presidio Hill. Eventually, Father Palóu reached Carmel Mission and in 1774 rejoined his old friend and mentor Father Serra. More hardships would follow but the Spanish settlement of California had by now been secured.