Miguel José Serra, a Franciscan missionary to the Indians of California was born November 24, 1713, at Petra on the island of Maiorca (Spain). He was the son of Antonio Nadal Serra and Margarita Rosa Ferrer who married in 1707 and spent their lives as farmers on the island.

Early life in Maiorca

When he was 7 years old, Miguel worked with his parents in the fields, helping cultivate beans and wheat and tending the cattle. In Petra, Miguel attended the primary school of the local Franciscan friary. At the age of 15, the parents enrolled him in the Convento de Jesús outside the walls of Palma, the capital city of Maiorca. He started his novitiate on September 14, 1730, and on September 15 the following year, he made his profession to the Franciscan Order.

The date of his ordination to the priesthood is not known, though it probably occurred in 1738. When he became a priest, he exchanged his baptismal name Miguel José Serra for the clerical one Junípero Serra. In 1742, Serra obtained his doctorate in theology from the Lullian University at Palma and started teaching philosophy at the Convento de San Francisco. Among his students were two fellow future missionaries to the Americas, Francisco Palóu and Juan Crespí.

Serra sails to America

On April 13, 1749, at the age of 36, Serra and a group of Franciscan missionaries sailed for America. Among them was Francisco Palóu who became Serra’s first biographer. They landed in Veracruz, Mexico, on December 7, 1749, and took the Camino Real to reach Mexico City. It was a rough road, stretching from sea level through tropical forests, high plateaus, and volcanic Sierra mountains to an altitude of 7,400 feet (2,300 meters). Although horses were supplied for the friars, Serra and another companion, a friar from Andalusia, elected to walk the 250 miles between Vera Cruz and Mexico City. During the long trek, Serra injured his left foot, probably due to Tungiasis, an inflammatory skin disease caused by infection with the adult female sand flea Tunga penetrans. Serra never fully recovered from this wound which plagued him for the rest of his life.

Apostolate in the Sierra Gorda

A few months after he arrived in Mexico, an urgent call came for volunteers from the Sierra Gorda Indian missions. The missions were nestled 90 miles north of Santiago de Querétaro, in a vast region of jagged mountains. The area was the home of the Pame Indians who so far had eluded conquest by the Spanish military. Serra was among the volunteers. During his apostolate in Sierra Gorda between 1750 and 1758, Serra expanded the missions in both religious and economic directions and learned to tackle the numerous challenges of mission administration. Crowning his Sierra Gorda period, Serra oversaw the construction of a magnificent church in Jalpan.

The Jesuits’ expulsion

On September 26, 1758, Serra returned to the College of San Fernando where he worked as a college counselor, master of novices, choir director, and confessor until 1768. Meanwhile, the King of Spain, Carlos III, had plotted the expulsion of Jesuits from the Spanish Empire. The Viceroy of New Spain, Carlos Francisco de Croix, enforced the Spanish royal decree in which all Jesuits had to be gathered in the port of Veracruz and returned to Motherland. In Baja California, the newly appointed governor Gaspar de Portolá gathered 16 Jesuit missionaries in Loreto from where they were deported to Mexico. At that time, the Jesuit priests had developed a total of 13 missions in Baja California over a period of 70 years.

Missions of Baja California

The Franciscan missionaries filled the void left by the Jesuits’ expulsion from Mexico. In July 1767, Serra was appointed president of the ex-Jesuit missions of Baja California by the guardian of the college of San Fernando. He was ordered to take up the Jesuit work and explore new fields. Serra headed a group of 15 Franciscan friars. Francisco Palóu was his second in command. In March 1768, the congregation of Franciscan friars boarded a Spanish sloop at San Blas, on Mexico’s Pacific coast, and two weeks later landed at Loreto after sailing over 200 miles up the Gulf of California.

After evicting the Jesuits, the Spanish military occupied the Baja missions and, upon their arrival, Serra and Palóu unpleasantly discovered that they ruled only on spiritual matters. Displeased with the mediocre administration, in August 1768, the new Spain’s inspector general, José de Gálvez, forced out the military and turned the missions over the full control of the Franciscan friars. The Franciscans discovered that epidemics, especially syphilis introduced by Spanish troops, were wasting the Natives and that Baja California’s indigenous population had dwindled to about 7,000. In his Father Serra’s biography, Father Palóu mistakenly attributed the ravages of syphilis to God’s retribution for the Indians’ murder of two Jesuit priests over 30 years earlier.

Exploration of Alta California

In 1768, the Inspector General of New Spain, José de Gálvez, decided to send explorers to Alta (Upper) California with the aim of settling the area. The move was a strategic one: on the one hand, Gálvez aimed at Christianizing the Native populations of Upper California; on the other hand, the settlement of Spanish missions and presidios would have prevented Russian expansion in the area from the North and protected America’s Pacific coast from possible claims by other imperial nations. Serra, now 55 years old, volunteered with enthusiasm and was appointed by Gálvez as the head of the missionary team in the expedition to Alta California. Serra was probably looking eagerly at the chance to harvest thousands of pagan souls in lands never touched by the Catholic church. We have detailed information about the expedition to Alta California as Serra wrote a diary of the journey.

The expedition party to Alta California was divided into five groups. Three groups traveled by sea and two groups by land in horse and mule trains. All groups departed from Baja California heading north for San Diego. Three galleons, the San Carlos, the San Antonio, and the San José, were hurriedly built in San Blas and set sail for San Diego in early 1769. All three ships started taking on water after crossing the Gulf of California and had to stop on the east coast of Baja California for repairs. The flagship San Carlos had a crew of 62 in all and was captained by Vicente Vila. The chaplain was friar Fernando Parrón. The cartographer Miguel Costansó also set sail on the San Carlos and drew the first detailed maps of Alta California. The San Antonio had a crew of around 30 men and was captained by Juan Pérez. Franciscan friars Juan Vizcaíno and Francisco Gómez served on board as chaplains. The San José followed the San Carlos and the San Antonio as a supply ship but never reached San Diego and went lost at sea.

The first land expedition was captained by Fernando Rivera. The group consisted of three muleteers, 42 Indian men from Baja California, and 25 Spanish soldiers. Friar Juan Crespí joined the group as chaplain and diarist for the Franciscan missionaries. Crespí met the Rivera party on Velicatá, then the northern frontier of Spanish settlement in Baja California. From there, the group set out for San Diego on March 24, 1769. The second group by land was captained by Gaspar de Portolá. Father Serra joined the Portolá party as chaplain and diarist. The party consisted of muleteers, artisans, and 44 baptized Natives of Baja California acting as servants and interpreters to communicate with Indians along the way. 25 Spanish soldiers under the command of Sergeant José Francisco Ortega also accompanied the party.

As the Portolá’s expedition party gathered in Loreto though, Serra’s infirmity in his foot and leg worsened. The Spanish military commander, Gaspar de Portolá, tried to dissuade him from joining the expedition. So did his fellow friar and former student Francisco Palóu, deeply concerned about his condition. Portolá even wrote a letter to José de Gálvez to inform him about Serra’s serious health conditions. In the end, it was agreed that the Portolá party would have set off without Serra and that he would have followed and met them on the northern frontier of Baja California. Serra assigned Friar Miguel de la Campa as chaplain to the Portolá expedition and, on March 9, 1769, Portolá departed from Loreto heading north for San Diego.

Mission San Fernando Velicatá

On his solitary journey, Serra was accompanied by two servants, a Spanish soldier and a young man from Magdalena named José María Vergerano. Riding a feeble mule, Serra arrived at Mission San Borja on April 28, 1769. There he was welcomed with enthusiasm by friar Fermín Lasuén. On May 5, 1769, Serra stopped in the deserted church at Calamajué where he celebrated a Mass for the feast of the Ascension. Continuing north, the next day Serra reached Mission Santa María de los Ángeles. There, he met up with the Portolá party. On Sunday, May 7, 1769, Serra celebrated high Mass at the mission church of Santa María, the utmost frontier of Spanish Catholicism. Heading north, Serra arrived at Velicatá by late evening of May 13. On May 14, 1769, the Pentecost day, Serra founded Mission San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá, also known as Mission San Fernando Velicatá or Mission Velicatá. Mission Velicatá was the only mission founded by Franciscan missionaries in Baja California.

Resuming the northern trail, Serra found it very hard to stay on his feet as the inflammation of his left foot had reached halfway up his leg. Again, Portolá asked Serra to withdraw from the expedition. Serra strongly refused and said he was ready to die on the way if this was God’s will. In the end, Portolá had a stretcher prepared and the Christian Indians traveling with the party carried Serra along the trail. Even though he usually avoided medicines, Serra asked the muleteer Juan Antonio Coronel if he could prepare a remedy for his wounds. Coronel applied the same remedy he used to heal his animals’ wounds and the next day Serra felt much better and found out that the swelling had stopped. At that point, 300 miles (480 kilometers) still divided them from San Diego. They progressed through deserted lands and oak savannas, camping and sleeping under large oaks. On June 20, 1769, the advance scouts saw the Pacific Ocean from a high hill. The Portolá party reached the shores of the Ocean on the evening of the same day and named the spot Ensenada de Todos Santos (All Saints’ Cove), today simply known as Ensenada. They were now about 80 miles (130 kilometers) from San Diego.

Serra arrives at San Diego’s Bay

On July 1, 1769, after trekking more than 900 miles (1,400 kilometers), Serra and the Portolá party finally arrived in San Diego. The Rivera party and friars Juan Crespí and Fernando Parrón had reached San Diego a few weeks earlier. The San Carlos and the San Antonio galleons had also reached San Diego while there was no news of the supply ship San José. The San Antonio arrived three weeks earlier than the San Carlos. The San Carlos had failed to recognize San Diego’s Bay and bypassed it by almost 200 miles before doubling back south. When it eventually reached San Diego’s Bay, the San Carlos had sailed almost four months since it had departed from La Paz, and its crew was devastated by scurvy. Upon arrival, on April 29, 1759, the galleon had to be boarded to help its surviving crew ashore.

The five expeditions totaled about 300 men but only half of them reached San Diego’s Bay. Most of the Indian Natives from Baja California recruited in the overland parties had either died or disappeared along the way as soon as military Spanish officers started to deny them rations because of food shortages. Nearly half of those who made it to San Diego were seriously ill and unable to resume the expedition. Doctor Pedro Prat, who had sailed on the San Carlos, was the expedition’s surgeon and made the greatest possible efforts to treat the ill men but he was weakened himself by scurvy. Despite his efforts, many of the ill men perished in San Diego. The chronicle of the hardships encountered in San Diego by the first European settlers of California is narrated here.

Father President of Alta California

On July 16, 1769, Serra founded Mission San Diego de Alcalá, the first of the twenty-one California missions, in a simple shelter serving as a temporary church. Serra’s adventure in Alta California had started. In 1770, Serra moved to the area that is now Monterey and founded Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo. A year later, he decided to relocate mission Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo to Carmel Valley. The mission also became known as Mission Carmel and Serra used it as headquarters during his Presidency of Alta California.

He devoted the next 15 years of his life to evangelizing the Native Americans of Alta California. As Father President of Alta California and, with the help of other Franciscan Missionaries, Junípero Serra founded the missions of San Diego de Alcalá in 1769, San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo in 1770, San Antonio de Padua in 1771, San Gabriel Arcángel in 1771, San Luis Obispo de Tolosa in 1772, San Francisco de Asís in 1776, San Juan Capistrano in 1776, Santa Clara de Asís in 1777 and San Buenaventura in 1782.

During the last three years of his life, he traveled more than 600 miles to visit once more the missions from San Diego to San Francisco and to confirm all who had been baptized. He confirmed 5,309 baptisms. With a few exceptions, most of the baptized were California Indian converts living at the missions.

Death of Junípero Serra

On August 28, 1784, Junípero Serra died at Mission San Carlos Borromeo from tuberculosis. When he died Serra was 70 years old. He was buried at Carmel Mission the next day under the sanctuary floor. Following Serra’s death, Fermín Lasuén became the President of the Franciscan missionaries in Alta California. By the end of 1784, Indian baptisms at the first nine missions had reached the number of 6,736, while 4,646 converted Indians were living in them. Today, the life of Serra and the heritage he left are studied in California schools.

Canonization of Junípero Serra

The cause for the beatification of Junípero Serra was formally opened on October 21, 1951, and granted him the title of Servant of God. During the process of Serra’s beatification, questions were raised about how Native Americans of California were treated while Serra was in charge as Father President of the missions. In 1948, the famous historian Herbert Eugene Bolton gave favorable evidence to the case, followed by five other historians whose judgment was solicited in 1986. On September 25, 1988, Serra was beatified by Pope John Paul II. On September 23, 2015, as part of the pope’s first visit to the United States, Pope Francis canonized Saint Junípero Serra during a Mass in Washington, DC. It was the first canonization to take place on American soil.

Criticism

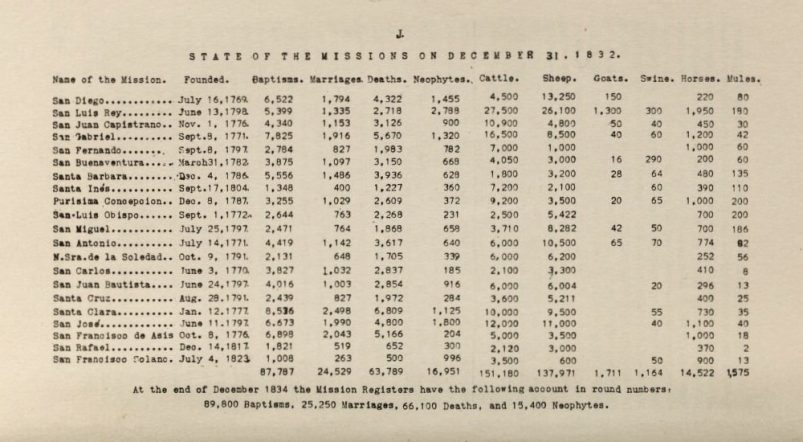

Many Americans, in particular Native Americans, have strongly criticized Serra’s canonization. Most of the critics refer to the fact that Serra and his mission system helped to erase and destroy the culture of Native Americans. While this is undoubtedly true, it remains difficult to ascertain where Serra stands on this. The Spanish colonists brought such enormous changes to the local ecosystem that it became impossible for Native Californians to continue with their traditional lifestyles. Native Americans perished in huge numbers, decimated by the diseases that the Colonists brought with them. The numbers speak for themselves: prior to the mission era, about 300,000 Native Americans lived in Alta California. By 1845, scholars estimate that their number had halved to 150,000. Moreover, studying the registers of births and deaths of the California missions, historians discovered that Natives’ death rates were overly high. From 1769 to 1832, 87,787 baptisms and 63,789 deaths of Native Indians were registered at the Missions of Alta California, showing an extremely high death rate.

The high rate of death in the mission system can be attributed to several factors, including diseases, undernourishment, and overworking. Inside the missions, Indian neophytes were often forced to sleep together in close quarters, which helped to spread diseases, the most common being fevers, dysentery, and venereal diseases. Nevertheless, some note that living at the missions became for the Native Indians the less terrible option among terrible options. Historical records suggest that Serra defended the Native Indians on more than one occasion against the cruelty of Spanish soldiers and officials. At times, Serra seemed more concerned with the Natives’ well-being than his Spanish peers. Nonetheless, his kindness toward Indians also appeared to be conditional on whether they accepted Catholicism and European-style living within the missions. Despite his best intentions, it is hard to deny that Serra’s efforts were made with the intent of assimilating Native Americans into “his own idea of civilization”.