Mission San Buenaventura was founded by Father Serra on the Easter Sunday of March 31, 1782. The site had been discovered and claimed for the Spanish King by the great navigator Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, almost 50 years after the landing of Christopher Columbus in the Western Hemisphere.

A Mission between San Diego and Monterey

According to plans made at Loreto before the first expedition started for Alta California, the Spaniards judged a third mission would soon be needed halfway between San Diego and Monterey. The Spaniards intended to establish this station at Mission San Buenaventura. Once in California, however, circumstances intervened, and it was 1782 before the opportunity for founding this mission occurred. In March of that year, a conference of some importance took place at Mission San Gabriel. Present were Father Serra, three of his Franciscans, Governor Felipe de Neve, and the ex-sergeant, José Ortega, now a Lieutenant after Father Serra’s unsuccessful campaign to have him appointed Governor of California.

Serra and de Neve conference at San Gabriel

The meeting between Father Serra and Felipe de Neve was of utmost importance to the Franciscan Missionaries, for the Governor had been in the territory for almost five years and now, for the first time since his arrival, agreed to discuss the establishment of a new mission. Father Serra had received word that six new Franciscan Padres were being sent from the College in Mexico City, but other difficulties needed to be solved.

The Franciscan Missions are expensive

From the point of view of the royal authorities in Mexico, new missions in the California style were expensive. The first missions had been supplied in part with goods taken from the Jesuit missions of Lower California; now, each new mission had to be provisioned with materials purchased and shipped from Mexico City. European wars were draining the Spanish treasury, and all available funds were being sent to the Mother Country. California, other than for its strategic position, meant little to the Spanish Crown and offered nothing in the way of material profit. From the King’s standpoint, mission expenditures were unnecessary.

Franciscans, Pious Fund, and King of Spain

The Franciscans took the position that the money spent was taken from the Pious Fund, a fund collected privately by their predecessors, the Jesuit Missionaries, solely for the purpose of maintaining the missions of Baja and, by extension, Alta California.

Such an attitude received little sympathy from the Spanish Crown and its Viceroy, for, by the Patronato that Pope Alexander VI issued in 1493, the King was given a free hand, based on law, over certain temporalities and appointments in administering the Catholic Church in the New World. Therefore, he argued that the Pious Fund was to be administered at his discretion. For the moment, the King of Spain did not desire to spend additional money in California.

Secular and Religious Powers Conflict

The position of the Spanish Crown led it to support the civil point of view. If Alta California could be colonized by merely distributing land to the newly arrived settlers, it meant a much less expensive way of protecting the area from foreign encroachment. As the Governors had long been arguing, a small white population was of far greater value to the Crown than any number of unpredictable Indians.

The enforcement of new secular regulations

The Yuma uprising also furthered Spanish distrust of the Indians, and the policy was soon embodied in a code of authority by Viceroy Bucareli. From this code, Felipe de Neve fashioned new regulations that ordered that all future missions be set up in the Arizona style favored by Commandante de Croix. This directive meant, of course, no mission industries founded on Indian labor and also only one Father to a mission.

Franciscans battle against the enforcement

The meeting at Mission San Gabriel must have been a difficult one for both Father Serra and the Governor. The new regulations had been published and Father Serra was aware of de Neve’s part in forming them, yet his College of San Fernando was still doing a valiant battle against their actual enforcement.

Founding of San Buenaventura is agreed

Father Serra and de Neve agreed on establishing two new missions, however, one at the site designated for Santa Barbara and one at San Buenaventura. Felipe de Neve planned to accompany the settlers, for he was interested in Santa Barbara, which also was to have a presidio. After the party was one day out, a courier arrived with orders from de Croix, bidding de Neve to meet with Pedro Fages, who was coming from Sonora, to campaign against the rebellious Yuma Indians.

Mission San Buenaventura is established

In de Neve’s absence, Father Serra chose to ignore the possibility of conflict with him and proceeded to build Mission San Buenaventura according to the original plan. When de Neve arrived sometime later, everything was running smoothly, and the friendly Indians of the area had joined in the many phases of mission life, though none had become neophytes. While Felipe de Neve said nothing about the establishment of the mission in defiance of the new code, the incident delayed the establishment of the next mission at Santa Barbara.

Prosperity of Mission San Buenaventura

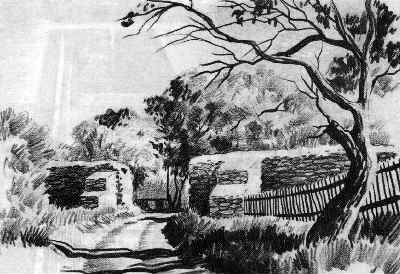

From the first, Mission San Buenaventura grew with extraordinary vigor. The Indians of the area, which the Spanish named the Channel Indians, were exceptionally able and energetic. By 1809, San Buenaventura possessed a great stone and masonry church. A reservoir and aqueduct system seven miles in length was built to supply water to the grain fields, which extended to the very edge of the Pacific Ocean.

The account of its prosperity left by the English sea captain George Vancouver, who visited the mission in 1793, credited it with an astounding variety of agricultural products. The mission was as fortunate in its Padres as in its Indians, for among them was Father José Senan, who afterward served as President of the California Missions.

Difficulties at Mission San Buenaventura

An earthquake in 1812 damaged the stone face of the mission church, and reconstruction work required nearly three years. After that, the mission suffered no disturbance until 1818, when it was abandoned for approximately a month because of the violence visited upon the area by Bouchard, the French pirate. In May 1819, attempts on the part of the mission guard to prevent a party of 22 Mojave Indians from fraternizing with the mission neophytes led to an outbreak that resulted in the death of ten of the Mojaves and two soldiers. The remaining Mojaves escaped, and though Mission San Buenaventura was spared any direct retaliation, the Mojaves became bitter and costly enemies of Spain.

By 1836, the mission was caught in the vortex of the social disruption that followed the Mexican revolt. In March of that year, it was the scene of a battle between supporters of the two leading aspirants for the “Governorship” of the province, and long thereafter its walls bore the scars of this conflict.

Secularization at San Buenaventura Mission

Secularization, which officially took place in June of 1836, resulted in a more gentle transition than that occurred at the other missions. The basic reason was that Rafael Gonzales, the first administrator, proved to be honest and efficient. By the middle of 1845, however, its lands had been completely broken up and sold. The church and a small part of its possessions were not returned until 1862.

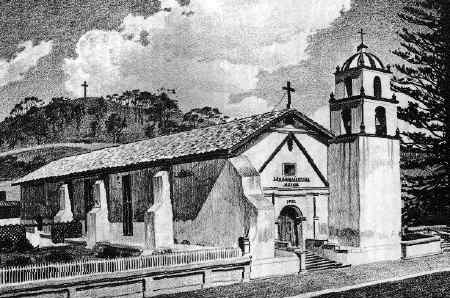

Mission San Buenaventura today

Today, Mission San Buenaventura has been engulfed by the city that grew up after the arrival of the railroad in 1887. The two great Norfolk Island pines that stand before it have an estimated age of well over 100 years. They reputedly were planted by a sailing captain in the hope that a forest of such giants would eventually provide a ready supply of ship masts.

The mission museum boasts a compact and interesting display of missionary relics. Among them are the remains of two old wooden bells, used in early ceremonies, and the only ones of this type known in California. Outside the museum building stands an ancient olive crusher designed for one-horse operation. The church exterior best represents its earliest appearance for the Indian handiwork that once graced the walls and altars within has been obliterated by the labors of a later day “improver.”