On the first day of June 1770, the Spanish packet San Antonio put ashore into the vast pine-bordered harbor of Monterey. It took the ship over a month to cover the more than 400 miles from San Diego. Once ashore, the passengers, with Father Junípero Serra at their head, were surrounded by the men of Governor Portolá’s land expedition. The latter group, which left the southern mission after the sailing of the San Antonio, had arrived more than a week before. During their wait, Portolá realized that he had camped on the shores of Monterey Bay on his previous journey without recognizing the harbor.

Founding Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo

After the joyous religious ceremony that accompanied the raising of the Spanish flag, held on June 3, 1770, news of the occupation was immediately dispatched overland to the authorities in Mexico. Within a few weeks, the Spanish party erected a church and the military Presidio before settling into an ordinary business-like routine. The heavy stands of forest surrounding the settlement made adequate housing easy to construct. Rough as it was, it presented an almost luxurious contrast to the mud and brush shelters in San Diego. Father Serra found the climate and surroundings of Monterey so much to his liking that Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo became his favorite mission and the headquarters of the growing mission chain.

Mission San Carlos is moved near Carmel River

In July 1770, Gaspar de Portolá turned his command as Governor over to Lieutenant Fages and departed forever from the pages of California history. The new military Commander was unlike the easy-going Portolá and immediately began to inject himself into mission affairs. Soon, Father Serra decided that the newly established religious settlement was more likely to prosper at a distance from the Presidio, and, in 1771, he moved Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo some five miles south to a verdant pasture bordering the Carmel River.

The Royal Presidio Chapel of Monterey

The church at the Monterey Presidio continued in use for the soldiers of the Garrison until 1794, when a newer structure, still in use today as a place of worship, replaced it. Today, the church at Monterey is known as “San Carlos Cathedral”, “Monterey Historic Royal Presidio Chapel”, or “Monterey Old Mission Chapel”.

Carmel Mission relies on supplies from Mexico

After the Franciscan Missionaries had settled in the new mission, life was divided between short intervals of sufficiency followed by long waits for additional supplies from Mexico. This situation continued until agricultural efforts flourished in the late 70’s. In 1774, during the visit of Juan Bautista de Anza, who had led the first overland party from Mexico, Father Palóu’s embarrassment at the lack of provisions for his guests finds eloquent expression in his diary. Nevertheless, the mission boasted 165 Indian converts by the end of 1783.

Tensions with new Governors of California

In May 1774, upon his return to Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo after a journey to Mexico, which required about a year and a half, Father Serra found himself increasingly in the defense of his missions. He lived in a little hut adjacent to Mission Carmel, where he pursued the life of an ascetic and administered the affairs of the growing mission chain. During his conferences with the Viceroy in Mexico, he had achieved in removing Fages as Governor of Alta California. However, new Governor Rivera y Moncada, who followed Fages, was even more difficult to deal with. Darker days would ensue after Rivera’s removal to Loreto and the arrival in Monterey of Governor Felipe de Neve.

The moving of the Capitol from Lower California to Monterey was followed by the transfer of California affairs from the friendly Viceroy, Antonio María de Bucareli, to the newly created office of Commandant-General, occupied by Teodoro de Croix. The latter, more concerned with other fields of colonization efforts in the Californias, was inclined to rely upon Felipe de Neve. Felipe De Neve’s opposition to the Franciscan Missionaries and their chain of missions was not like the hostility that the military Commanders Fages and Rivera had displayed so far.

Felipe de Neve, 4th Governor of the Californias

Felipe de Neve seems to have regarded mission colonies simply as an outpost of the Spanish empire and was not personally interested in the welfare of the Indians, whom he distrusted. He was anxious to transform California mission establishments into thriving communities, well-populated with citizens of Spanish blood. To accomplish this, de Neve encouraged immigration from Mexico and began to force the Franciscan Fathers out of colonial life. He intended to phase out the Missionaries from their political and economic control over the missions.

Growth of the mission chain is halted

Father Junípero resolutely opposed Felipe de Neve, and while he succeeded in defeating the Governor’s aggressive acts against the established missions, the struggle caused a long delay in mission expansion. As a result of these divergencies, the Franciscan Fathers established only one new mission, San Buenaventura, between 1777 and December 1786.

Father Junípero Serra dies in 1784

Already illustrious names connected with the early days of the missions were beginning to pass. Father Crespí, the constant journalist of those Spartan beginnings, died in 1782. A year later, Father Serra, in his seventieth year, made his last journey down El Camino Real and then settled back in his beloved Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo to await the end he knew would not be long in coming.

He died on August 28, 1784, attended by his old friend and life-long companion, Father Palóu. Father Junípero Serra had devoted 54 years of his life to the cause of Saint Francis, of which the last 15 in California had been the most demanding and exacting. He did not live to witness the mission prosperity or the imposing structures we see today, but they are a part of him more than any other.

Headquarters remain at Mission Carmel

After Father Junípero death, Carmel Mission remained the “Parent” mission. Father Palóu became President of the California Missions pro tempore until he retired to Mexico in 1785. The same year, his successor, Father Fermín Lasuén, became President at the age of 49. He actively guided the Spanish missions of California for almost 20 years, and it was under his administration that they reached their greatest prosperity. During most of this period, he lived at Mission Carmel, which developed considerably under his direction, although its success never approached the impressive proportions of some of the later missions.

Secularization halts Carmel Mission’s expansion

Seated as it was, in the shadow of the Governor’s office, Mission San Carlos Borromeo del Río Carmelo was always the first to endure the effect of each new mood for “mission reform”. As the secular pressure for divorcing the Franciscan Missions from their rich holdings increased, the properties of Mission Carmel diminished. When the act of secularization finally came, not even the buildings remained in her name.

Michael D. O’Connell and Harry W. Downie

From 1836 until the property was restored to the Roman Catholic Church by the United States of America, the mission lay abandoned and decaying. In 1882, an effort was made to preserve the existing ruins, but nothing further was accomplished until 1924, when part of the structure was restored. The mission became a parish church in 1933, and since then, the property has been undergoing a series of restorations. Today, it is one of the most eminent historical landmarks on the California coast. The restoration work was primarily the result of two men, Father Michael D. O’Connell, pastor of the church after 1933, and Harry W. Downie, one of the leading authorities on mission architecture and reconstruction.

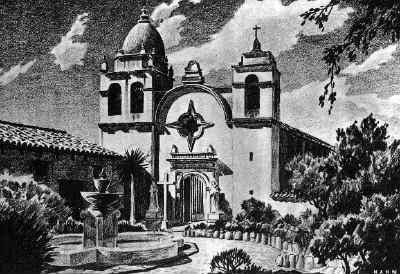

Majesty of San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo

Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo has recaptured much of the majesty of its happier days. Set apart from too much evidence of the modern world, the atmosphere surrounding it seems haunted by an ancient solemnity that emphasizes its connection with the past. A rude wooden door leads visitors from present times into yesteryear as they enter an ancient room where historical treasures are displayed. An array of implements and garments, carefully fashioned by patient hands with unhurried hours, reveal the hardiness of early mission life.

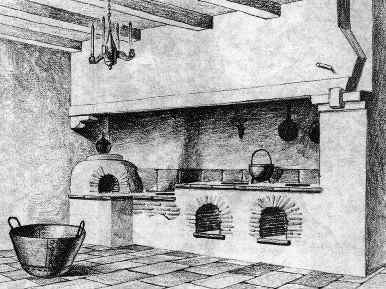

One room contains a complete reproduction of an early mission kitchen. The curio rooms are plenty of crude tools and examples of impressive basketry of the Indian neophytes. Here and there, among the statuary and ceremonial articles brought to Mission Carmel from Mexico is a native Indian carving, a gaunt and arresting consequence of welding two alien cultures.

Outside, a walk leads through the beautifully kept gardens to the Serra Chapel, constructed in his honor. Inside the Chapel is the sarcophagus created by the California Artist Jo Mora and dedicated to the Franciscan zeal. Both the Chapel and the Cenotaph memorial in bronze and travertine were completed in 1924.

The stone church of Mission Carmel

Just beyond stands the imposing stone church, built under the direction of Father Fermín Lasuén in 1797. The use of stone, shared by only three other churches in the mission chain, San Gabriel Arcángel, San Juan Capistrano, and Santa Barbara, represents a departure from the usual adobe structure. However, the rounded catenary arch that forms the roof and the Moorish influence reflected in the tower dome are singular qualities of structural beauty that belong to Carmel Mission alone.

At the foot of the altar of the church are buried the earthly remains of Fathers Junípero Serra, Juan Crespí, Fermín Lasuén, and Julian Lopez. Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo is today one of the most stunning and enlightening in the whole California Mission chain.