In 1771, the arrival of 10 more Franciscan Missionaries at the headquarters of Father Serra in Monterey gave new impetus to his plans. Immediately, he moved to close the long gap between his own San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo near Monterey and the Mission at San Diego, far to the south. In the summer of the same year, Father Serra decided to establish two new missions, the first, San Antonio de Padua, a day journey south of Carmel, and the latter, some convenient distance north of San Diego. This second mission, fourth in the chain, was to be called San Gabriel Arcángel.

Founding of Mission San Gabriel Arcángel

Late in the summer, two Franciscan Missionaries selected by Father Serra, Fathers Pedro Cambón and Angel Somera, arrived at the proposed new site on the “Rio de los Temblores”, now called Santa Ana River. Once at the spot, however, the Missionaries decided they could find a better location and pushed on until they crossed the San Gabriel River. Here, they found a desirable spot for Mission San Gabriel Arcángel near the present town of Montebello.

On September 8, 1771, Mission San Gabriel Arcángel began the colorful and eventful existence which it continues to enjoy. The mission prospered from the first, and the Indians, attracted by the solemn pageantry of the Franciscan Mass, grew eager to participate in the religious rites and helped erect the walls. Conversions through Baptism, the ultimate ambition of all the Franciscan Fathers, began on the second day.

The Padres dissuade Natives from revenge

All this good feeling was not to continue without interruption, for the military guards were unhindered by any ideals of decency in their attitude toward the Indians. Soon, the Spanish guards provided the good Fathers with an anguishing embarrassment. One of the military “protectors” forcibly conquered the wife of an Indian Chieftain and proceeded to silence his objections with a gunshot. The brutal occurrence aroused the Indians, and only a quick and decisive conciliatory action by the Padres averted bloody retribution. The Spaniards pushed the guilty soldier to another station, and after a short time, the good feeling that once existed between the Fathers and their Native converts returned.

Juan Bautista de Anza and the first land route

On March 22, 1774, Juan Bautista de Anza and his expedition of colonists arrived at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, thus establishing the first land link with Mexico City. Thanks to the opening of this route, the long and perilous sea journey around the peninsula of Baja California could now be avoided. San Gabriel Arcángel became the chief point of contact in Alta California for colonists arriving via land from Mexico, and its importance increased.

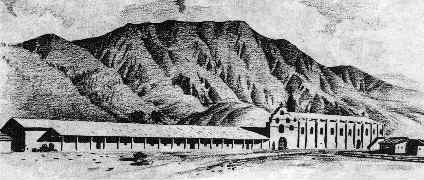

The Mission is moved where it stands today

In 1776, the Franciscan Fathers moved Mission San Gabriel Arcángel five miles to the northwest and rebuilt it on the broad, fertile plain where it stands today. In the same year, the Mission Fathers began the construction of the present buildings. At its new location, San Gabriel Arcángel became the wealthiest and most prosperous of all missions. The main difficulty was a long series of exasperating annoyances visited upon the mission and its Indian neophytes by the secular colonists established at the nearby pueblo of Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles de Porciúncula, now Los Angeles, the third largest city of America.

The exploitation of Mission properties

The land-hungry military and political figures of this swiftly growing civilian colony, long attracted by the power and property of the missions, found a means of exploitation. Spain had been cut off from its colonies in the New World by its long involvement in the Napoleonic wars and the destruction of its naval forces. Left adrift, the people of Mexico found they could get along without the Mother Country, and a struggle for the vacant chair of authority developed. Mexico became a Republic, though hardly stable, for the occupants of the Presidential Palace changed frequently, and the policies of the Legislature varied from week to week.

Under these circumstances, influential Mexican Californians welcomed the passage of the controversial decrees of secularization. Although the decrees gave the Indians nominal possession of most of the mission lands, the California Dons quickly discovered that the new beneficiaries had no relish for the joys of private ownership. The properties soon shifted into the hands of families closely involved in the military and civil rule, who succeeded in getting themselves appointed as Administrators under the laws of secularization.

San Gabriel Arcángel and Secularization

In November 1834, Mission San Gabriel Arcángel was turned over to the Civil Administrator. The inventory at the time included more than 16,500 cattle. In less than six years, no more than a hundred remained on behalf of the mission. By 1843, when the Franciscans were allowed to return temporarily, the Padres discovered that all mission valuables had gone lost. In 1853, the Franciscans left for the last time. The final sale of the property, which California Governor Pío de Jesús Pico had arranged, was stopped by the arrival of United States troops. In 1862, the mission buildings and part of the adjacent properties were restored to the Catholic Church by an act of the American Congress.

Mission relics and Indian paintings

Today, Mission San Gabriel Arcángel possesses one of the finest collections of mission relics. Of great interest is the series of Indian paintings representing the Fourteen Stations of the Cross. Strikingly primitive, these canvasses are probably the oldest existing examples of Native Christian painting. The colors, obtained locally from wild flowers and mixed with olive oil, seem to have weathered the years more successfully than the paintings the Padres brought to the Mission from Spain. In these paintings, there is more than a hint of the mural technique characteristic of the modern Mexican school of art.

The painting collection includes Mexican and Spanish works, with some over 400 years old. Several Spanish paintings have been attributed to the school of Murillo, and the Master himself is likely represented in one of the artworks. Fifteenth-century Italian paintings are a portrait of the Virgin Mary by Correggio and several early copies of Raphael and Andrea del Sarto. The museum collection also boasts several ancient wooden statues, probably Spanish in origin, and handwrought objects of copper, brass, and silver forming a considerable part of the antique display.

Mission tour and ancient gardens

A tour of the mission grounds takes the visitor immediately into ancient and peaceful gardens. Facing the entrance is the fountain added by the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West in 1940. Along the border of the garden, where long green grasses wash against the buttresses of the ancient church, several of the early Fathers lie buried along with thousands of their Indian disciples. The Camposanto, or cemetery, was first consecrated in 1778 and is still used as a burial ground by the Claretian Fathers, who now administer the mission.

Buttresses and heavy stone walls

Here and there in the gardens is mute evidence of the bygone wonders of San Gabriel’s busier days. The long tannery tanks that turned thousands upon thousands of hides into useful leathers, and the four huge tallow vats that produced candles and soap for all missions, are today only crumbling piles of neglected brickwork. They were once a part of the vast mission industry that made the barren California lands fruitful and habitable.

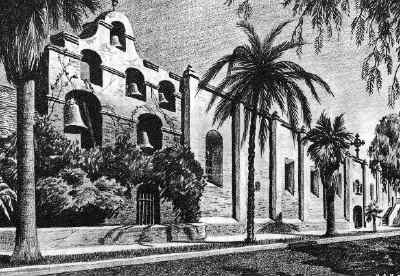

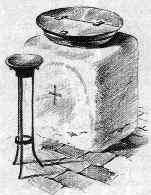

San Gabriel church was closed to the public for a time because of the recent earthquake damage, but mission treasures are intact, and the grounds remain open. The old baptistery, with its hammered copper font brought to the mission from Spain in 1771 as a present from King Carlos III, has been the scene of well over 25,000 baptisms. The interior of the long and narrow structure, except for the questionable addition of an oak-paneled ceiling and the enlarged windows, remains very much as it was in its earliest days.

The exterior of Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, with its huge buttresses and heavy stone walls measuring more than five feet in thickness, offers one striking departure from its original appearance: it has no bell tower. It was the accidental result of the earthquake of 1812, which destroyed it. In the reconstruction, the builders turned their back on the traditional mission bell tower in favor of the strikingly effective Campanario, which presently houses the ancient and massive bells. San Gabriel Arcángel, built of stone, brick, and mortar, is one of the best conserved among all California Missions.