The Genesis of Mission San José is connected to the development of El Camino Real. By 1796, El Camino Real had become a well-traveled highway that joined the northern extremity at San Francisco with the southernmost mission at San Diego. The road, however, stretched great lengths through areas occupied by hostile Indians whose presence made it necessary to furnish military protection for all but the boldest of travelers.

The Franciscans long held the hope of establishing a Mission at the end of each day travel along the road, and, with the arrival of the new Governor Diego de Borica from Mexico, Father Fermín Lasuén deemed the time ripe for the advancement of a new Mission. Accordingly, he conferred with the Governor, and the two agreed that five additional Missions were needed.

The Planning of five additional Missions

In August 1796, Borica forwarded a joint request to Viceroy Branciforte, remarking that the project would require no more soldiers than California presently had. Further, a saving of some $15,000 annually could be realized, because military protection against the Indians would not be needed once they were “reduced” by the Franciscan Fathers. The Viceroy saw no reason to restrain the planners and gave his permission to proceed.

Dedication of Mission San José

On June 11, 1797, Father Lasuén, accompanied by Sergeant Pedro Amador and five soldiers, dedicated Mission San José at a spot 15 miles to the north of the Pueblo which bore the same name and which had been founded by Lieutenant Moraga almost 20 years before. Mission San José was sufficiently removed from the Pueblo of San José de Guadalupe to relieve the attendant Friars of the anxiety that afflicted those Fathers whose Missions were too close to other colonial settlements.

The Hostile Ohlone Indian tribes

Problems of another sort would afflict the Missionaries who labored at Mission San José. The Ohlone Indian tribes of the area were either indifferent or openly hostile, and by the end of the first year, the Fathers had gathered only 33 neophytes into the compound. These were, for the most part, too young to do the badly needed construction work. By 1800, there were 286 Indians at Mission San José. After this date, the situation improved until 1831, when the Indian population reached 1,877. Then, it rapidly dropped until only 580 remained in 1840.

Indian tribes of San Joaquin Valley

Located east and south of San Francisco Bay, San José stood astride the approach to the San Joaquin Valley, where many hostile Indian tribes lived. Since it acted as a sort of halfway point, San Joaquin Valley became the headquarters of the Indian fighters. Forays against the Natives were frequent, the first occurring soon after the Fathers established San José.

The Franciscans had been aware for some time that a hostile Indian tribe was harboring a large number of runaway converts from the Mission in San Francisco. Sergeant Amador led an expedition against the tribe and, after a short battle, returned with over 80 runaways and 9 additional “pagans” captured in the fight. In 1805, another group of hostile Natives attacked a party of whites and killed four of them. The attack evoked a savage reprisal from the Spanish, who massacred 11 Indians and captured 30 more.

Indian Chieftain Estanislao

In 1826, the Indian fighters attacked the Cosumnes tribe, far to the north of the San José Region, and, in the ensuing battle, destroyed more than 40 of the belligerents. Three months later, a considerable force of Spanish soldiers and settlers led by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo marched against a large band of marauders headed by the Indian Chieftain Estanislao and his companion Cipriano. The two were fugitive neophytes from Mission San José, and Estanislao had been a favorite of Father Durán.

A band of over 1,000 Indian fighters

In May 1826, Vallejo and his army moved against Estanislao and his runaway band of over 1,000 Indians. The battle developed into a running fight that lasted nearly three days and ended in a complete victory for the Spaniards. Those of the enemy not killed outright were hung without further ceremony except for Estanislao, whom the Spaniards brought to San José Mission as a captive.

Estanislao returns to Mission San José

Father Durán was far from pleased with the victory and protested the Commandant’s violent treatment of the Indians. Father Durán received little satisfaction on the matter but secured the release of his former neophyte. Although authorities differ on the matter, some claim that the river beside which the fight occurred and the modern county through which it runs bear the name “Stanislaus” in memory of the renegade neophyte.

Father Narciso Durán at Mission San José

Father Narciso Durán first arrived in California from Mexico in 1806 and was assigned, with Father Buenaventura Fortuni, to Mission San José in that same year. Together, they labored for more than 20 years until Father Fortuni was called to Sonoma, leaving Father Durán alone in San José. Just before Father Fortuni’s departure, Father Durán was elected President of the Missions, an office he held from 1825 through 1827, and again from 1831 to 1838.

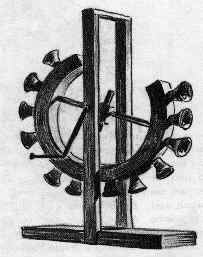

The orchestra of over 30 Indian musicians

Even today Father Durán’s administrative ability is compared favorably with that of Father Fermín de Francisco Lasuén, although his misfortune was to head the Missions at a time when they were fighting desperately for existence. While the mission system was already doomed when he assumed office, his brilliant leadership prolonged the useful life of the Mission establishments for many years. He was an accomplished musician, and his love for music led him to organize and train 30 Indian musicians proficient with several instruments, including flute, violin, trumpet, and drums.

A Zacatecan leads Mission San José

The Mexican revolt had cut off the arrival of further Missionaries from Spain, and the College of San Fernando in Mexico City suffered a decline because of the anti-Spanish feeling that developed in the New Republic. The Government of Mexico called on the Zacatecan College to supply additional Franciscan Missionaries. Governor Figueroa arrived in 1833, accompanied by several Zacatecans born in Mexico. The new Padres took charge of the northern missions, and Father Durán retired to Santa Barbara, leaving Mission San José in the hands of one of the arrivals.

San José Mission and Secularization

Only three years later, Secularization hit San José Mission, and the Administrator turned over its property to José de Jesús Vallejo, the brother of Mariano. When the transfer occurred, the mission property was valued at $155,000. Over two years, its value had entirely dissipated.

Hartnell, Inspector General of the Missions

William Hartnell, the former English man who became Inspector General of the Missions after the Secularization Act, voiced his opinion that the mission property could be found on the ranch belonging to the Vallejo brothers. However, nothing was done about the matter, and in 1846 Governor Pío Pico sold what was left of the property to his brother, Andres, and former Governor Alvarado. In 1858, the United States Government eventually nullified this sale, and the property, some 28 acres, was returned to the Catholic Church.

A new wooden church in Gothic style

A white frame church with a tall steeple was erected on the site in 1868, immediately after an earthquake and earlier neglect destroyed the original adobe church. A similar frame rectory rose between the church and a forlorn segment of the original monastery. In 1916, a wooden roof was erected over this portion of the monastery to protect adobe remains from further erosion. Inside the gloomy, unlighted rooms were a few relics of its industrious years: Mass bells, a Mission-Era tool, and some fading vestments. Only in the garden, at the rear of the monastery, was there a thriving reminder of the old Mission San José, a grove of olive trees.

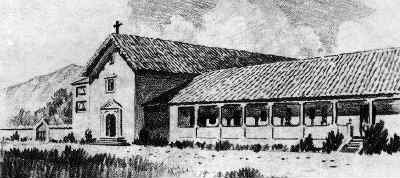

Replica of the 1809 Mission Church

In 1982, ambitious plans to rebuild the old Mission-Era church on its original foundation came to fruition. By 1985, the church was finished and rededicated, with the original portion of the old monastery strengthened and its museum improved. Today, the exterior of the Mission church appears much as it did when first completed in 1809, while the beautiful interior once again is decorated as it was during the 1830s.