For many years, Mission San Francisco de Asís had been plagued by the consequences of the damp and foggy weather that dominated the area. The Native Indians, especially after being exposed to several diseases, were inclined to waste away as the unfavorable weather retarded their recovery.

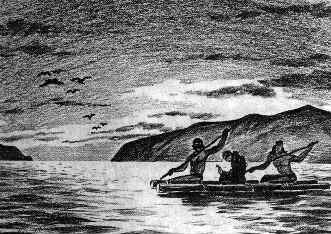

Finally, the Father Prefect, Sarría, was offered a plan for moving the weaker and more unhealthy neophytes to the warmer hill climate on the sunny north side of the bay. At first, Fr. Sarría did not feel that his charges would be able to withstand the temptation of the pagan rancherias, many of which were located in the wilderness of the northern bayside region, and he was inclined to delay his decision. However, when Fr. Luis Gil volunteered to preside over the proposed Asistencia, the father prefect gave his ready approval, for Fr. Gil was versed in medical science.

On December 14, 1817, the improvised sanitarium was founded under the patronage of San Rafael Arcángel, the angel of bodily healing. A number of the invalid Indians were transferred to the new settlement and, with a handful of converts attracted from the vicinity, they formed a neophyte community. By the end of the first year, the Asistencia had a population of over 300.

The outward appearance of the new settlement was far less imposing than the parent mission across the bay. It was a plain building, approximately 40 by 90 feet in floor area, divided rather casually into several rooms that served as a hospital, chapel, storeroom, and monastery. Since it was considered a mere branch of Mission Dolores, all records and vital statistics were kept there and the San Rafael Indians were included in the number of neophytes credited to Dolores.

Fr. Gil served the little hospital community for two years. At the end of that time, management of the station was placed in the hands of Fr. Juan Amorós. The new padre was a man of forceful character whose zealous and energetic example turned the neophytes to a more industrious way of life. Often he went far into the wilderness in his search for new converts, and, nearly as often, he would bring back one or two.

Before long, the little colony at San Rafael was a healthy community in which more than 1,000 neophytes were living. On October 19, 1822, San Rafael was declared independent of Mission Dolores and raised to full mission stature. The following year, Fr. Amorós became involved in a controversy with Fr. Altimira of Dolores over the question of abolishing both San Rafael Arcángel and San Francisco de Asís in favor of a new mission at Sonoma. The future looked bleak for the little settlement at San Rafael until it was decided to maintain missions at all three locations.

The proud new mission increased its efforts to produce prosperity in keeping with its rise in importance. The number of livestock grew to very respectable proportions and the areas under cultivation increased. Mission San Rafael Arcángel soon was noted for the quality of its pears. Unfortunately, the mission acquired its independence near the end of the mission period, just in time to face the full force of the political and social disturbances that were about to sweep it away.

At the end of 13 years of unrelenting labor on behalf of his Indian converts and his religious ideals, Fr. Amorós passed away. It was the year 1832 when his weeping charges laid him to rest and shortly thereafter the mission was transferred to the Zacatecan Franciscans and placed in the charge of Fr. José Mercado. The new padre was a man of violent temperament, and sensitive to any act of interference with his right to rule over the Indians of the mission. It was not long before he was engaged in a headlong conflict with General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, the Commandante of the San Francisco Presidio who was inclined to use his position to inject himself into the affairs of all the missions in the area.

Unhappily for Fr. Mercado, his uncompromising nature led him into other violent excesses, and the General, who was a good deal more clever than the friar, gathered up a good case against his enemy. Fr. Mercado was not a man to trifle with insubordinate Indians. He organized and armed a band of his neophytes and sent them against a group of savages who had scorned his efforts to convert them. The neophytes fell upon the unarmed band and killed in large numbers. This act, which had the effect of arousing the outlying tribes against all the whites, drew strong protests from the Spanish in the area. Vallejo brought Fr. Mercado’s action to the attention of Governor Figueroa, who was understandably indignant and secured the removal of Fr. Mercado from the mission.

San Rafael was the first mission to be secularized and the occasion followed hard upon the heels of Fr. Mercado’s departure. Given his earlier actions, it can hardly be a coincidence that Vallejo turned up as the official administrator. It is a fact, however, that he wasted no time in settling the mission accounts. All livestock was immediately transferred to his great ranchos, and this was followed by equipment and supplies. Even the vines and fruit trees were taken up and replanted on Vallejo property. The job was a big one requiring a good deal of labor. Therefore, as it was their mission, Vallejo hired the Indians to do the work!

Nonetheless, the general was also capable of many kindnesses. After he became the acknowledged ruler of the area north of San José, he was often gracious and even generous to his friends, the Americans or other foreigners who looked to him for land. He was concerned for the welfare of the men in his army and favored their advancement into the growing ranks of new landowners. In searching for the reason why Vallejo was such a bitter enemy of the missions, it is well to remember that he was exceedingly ambitious and that, under Spanish law, the missions held their lands in trust for the converted Indians. He was an enemy of the Indians because they had the land; he was an enemy of the Church because the church supported the idea of Indian possession.

Men like Vallejo were either unable or unwilling to spend the long years of labor required to build up the land. The riches existing in California at the time of their arrival were the product of the mission system. The only way they could acquire this wealth quickly was to take it from the missions. The Mexican secularization act, without the provisos that protected the Indians, was a simple solution to their problems, so Vallejo and the others adopted it. The real tragedy of the secularization program, however, lies in the fact that, with rare exceptions such as Vallejo, these men did not know what to do with the mission lands once they had obtained them.

For many years Mission San Rafael Arcángel was all but forgotten, its memory alive only in books and ancient records. In 1909, the Native Sons of the Golden West placed a mission bell sign at the site of the old mission and recently a new building was erected.