Mission Santa Cruz was founded on August 28, 1791, and dedicated on September 25 of the same year although Father Fermín Lasuén, who selected the actual site, was not able to be present at the dedication. The event, of considerable importance to Northern Californians, was attended by the Franciscan Fathers from Santa Clara and the Commandant of the San Francisco Presidio. His presence was a reflection of the vast improvement in relations between the friars and the military.

Franciscans and Governors Relations

The new Viceroy in Mexico City was sympathetic to the Franciscan cause, and best of all, in the eyes of the Padres, Governor Fages had departed in April of 1791. His successor José Antonio Roméu, was very ill when he arrived in California. He had only one year to live and, during this brief rule, was inclined to allow the Padres to follow their own counsel. The next Governor, José Joaquín de Arrillaga, was of a similar disposition, and the Franciscans did not have further conflicts with the military until the arrival of Diego de Borica in October 1794.

Santa Cruz is resettled on Mission Hill

The first Franciscans in charge of Mission Santa Cruz were Fathers Isídro Alonzo Salazar and Baldomero López. Initially, the Franciscans established Santa Cruz Mission at the bottom of Mission Hill, close to the intersection of River Street and North Pacific Avenue in present-day Santa Cruz City. With the arrival of winter, the San Lorenzo River flooded the Mission multiple times. The Fathers spent the following two years, until 1793, resettling Mission Santa Cruz to higher grounds on the top of Mission Hill.

Early years of Mission Santa Cruz

Despite that, the early years of Mission Santa Cruz were pleasant ones. Gifts from the older Missions poured in, and within three months, 87 Indian neophytes gathered in the growing community. The first permanent church, completed in 1794, was located on the heights overlooking the San Lorenzo River. The building was 112 feet long, 29 feet wide, and 25 feet high, with walls five feet thick.

Visitors to the missions often remark upon the long and narrow construction of the buildings. This design, which could almost be called the trademark of the missions, was dictated by the limitations that the Fathers faced in California. They had few who were versed in the art of engineering, and their Indian help could not be expected to follow the demands of intricate construction.

The width of the mission buildings was primarily determined by the length of the wooden beams that supported the flat roof since the adobe walls could not withstand much weight or side pressure. Only Mission Carmel, where Father Fermín de Lasuén had the assistance of an expert artisan, dared to depart from the usual flat and narrow structure.

Prosperous years of Santa Cruz

At Santa Cruz Mission, Padres erected other buildings, and the Mission enclosed a square. In 1796, Fathers and Indian Converts built a grain mill, after which they looked forward to further expansion. The same year, the population of Native neophytes also peaked, numbering about five hundred. Unfortunately, adversities prevented Mission Santa Cruz from real success and prosperity. Ultimately, the Mission Fathers came to look upon 1796 as their most prosperous year and pointed to the new Governor, Diego de Borica, as the cause of their misfortune since he founded California’s third Pueblo just across the river in 1797.

The Downfall of Mission Santa Cruz

When Father Francisco Palóu had crossed the San Lorenzo River in 1774, he was impressed by the character of the country about him. While its seaside location was considerably to the west of El Camino Real, which was developed after the establishment of Mission Dolores, there was little then that was not remote from existing habitation. The impressive sight of the full-flowing stream, the lush vegetation, and the heavy stand of timber moved him to remark that the site would be able to support a large and prosperous community. The Pueblo which took root there in 1797, did not prosper during the Spanish regime but did exist long enough to contribute materially to the downfall of Mission Santa Cruz.

Secular Pueblo of Branciforte

Villa de Branciforte, the new civilian community, can be considered California’s first real estate development. It was beautifully laid out on paper and launched with such grandiose enthusiasm and empty promises that it may have been the pattern for many present-day promotions. Borica began by asking the Viceroy to send him healthy, hard-working colonists, promising them neat, white houses, $116 annually for two years, and $66 annually for the following three. In addition, each settler would receive clothes, farm tools, and furniture.

California’s first real estate development

The community was plotted in the manner of an ancient Roman frontier colony, with all the houses arranged in a neat square. The farming area formed one huge field which was divided into smaller units, each assigned to an individual settler. When the new settlers arrived, they found that the houses had not been built. Diego de Borica, on the other hand, discovered that the newcomers were not quite what he expected. His subordinate commanding the Branciforte military was constrained to make the following report: ”… To take a charitable view of the subject, their absence for a couple of centuries at a distance of a million leagues would prove most beneficial to the province.”

The Pueblo turns into a failed social experiment

Indicative of the nature of the new community was one of its earliest public works: a race track. Perhaps the new settlers were more suited to the country than the unhappy commander realized, for, like many of the original Natives, they much preferred to relax and spend their time gambling rather than pursue any demanding industry. Branciforte was conceived as a sort of 18th-century welfare state with the Spanish idea of mixing the races, which had proved so effective in colonizing other provinces in Latin America. Each alternate house was earmarked as a residence of an Indian “chief.” The Spaniards believed such an arrangement would hasten the development of the Native Indians into ideal Spanish citizens.

While the plan had worked admirably in some parts of Mexico, California had no real Indian Chiefs. What leaders there were, presented a dismal contrast to the resplendent kings of the Indian civilizations of the south. Indians did come to the Pueblo of Branciforte, but not as fellow citizens. Usually, they were runaway neophytes from across the river who were soon ensnared by the pleasures of the aguardiente bottle and pressed into service by the indolent whites.

Mission Santa Cruz begins its decline

Of the five hundred Indian neophytes at the Mission in 1796, some two hundred melted away in less than two years. In vain, Father Lasuén complained that the new town was encroaching upon mission lands. The Governor, with remarkable logic, pointed out to the Father President that the mission lands belonged to the neophytes and, therefore, the fewer neophytes in the Mission, the less land the Mission would require. Unable to retaliate against the hated Pueblo, the Fathers did not hesitate in applying swift justice to the Indian backsliders they were able to regather in the fold. The severity of these punishments probably accelerated the decline of Mission Santa Cruz.

Citizens of Branciforte loot the Mission

The happy days at Santa Cruz were over. In 1818, the news of Bouchard’s attack on Monterey at the south end of the harbor was accompanied by orders to strip the Mission of valuables and retire to Santa Clara until the danger was over. In the process of “saving” the Mission, the inhabitants of Branciforte, who volunteered for this patriotic duty, managed to inflict more damage than a fleet of pirates could have done. Anything not lost or stolen was smashed or buried in such a manner that it was beyond further use. So great was the indignation of the Franciscan Padre in charge that he argued for the abandonment of the Mission.

The hide and tallow trade with smugglers

During the remaining 15 years of its operation, Mission Santa Cruz led an exciting existence. The Pueblo of Branciforte naturally attracted many of the rough foreign adventurers who were beginning to arrive on the shores of California. Located, as it was, on Monterey Bay, yet out of sight of the Governor at the Monterey Presidio, Santa Cruz developed a trade with the hide and tallow smugglers.

Later, after restrictions were removed, its activities centered around the hide trade until the commerce was put out of business by the Secularization Act in 1834. There was an attempt at some sort of land distribution for the Indians, but in 1845, Santa Cruz had become a small settlement of about 400 citizens, and only one-fourth of them were Indians.

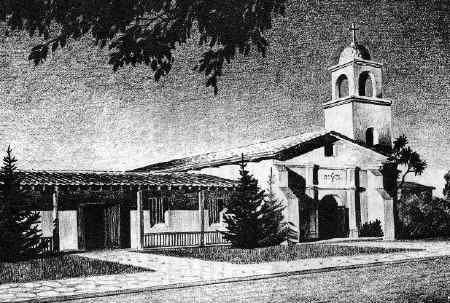

Mission Santa Cruz today

Today, the lovely city of Santa Cruz occupies not only the site of the old Mission but that once graced by Branciforte as well. Only a street name commemorates Branciforte, and at the approximate site of the Mission, there stands a modern chapel built in the exact proportion, though half the size of the adobe mission church that once welcomed the arrival of its first Indian neophytes more than two hundred years ago.